Request a Gifts in Wills information pack

In conversation with Professor Ian Pearce

Tell us about your career as a retinal specialist:

“I’ve been a consultant ophthalmologist for 22 years, and I’m the Director of the Clinical Eye Research Centre in Liverpool. I trained in Manchester, Liverpool and Leeds as an ophthalmologist, but I made it clear that I wanted not only to bring the clinical element to my profession, but the research side too. So I’ve always been actively involved in research, which is also at the heart of our profession.

“At the research centre, we attract commercial trials from large pharmaceutical companies like Roche, Bayer, Novartis etc. They will approach us with a new treatment and we will conduct the trials and run those studies carefully and appropriately, so we’re treating the correct patients.

“One of the things that makes me most proud of having a clinical eye research centre here in Liverpool is that if you live locally in one of the very deprived areas, you can get the same access to treatment as you would if you were living in an apartment in Manhattan, or in a pleasant suburb of Sydney or Berlin. Because we’ve got the facilities, we’ve got this department, local and regional patients have access to the latest developments. And of course everything we do at the research centre will benefit people with macular disease all over the country – and globally.”

After 22 years in ophthalmology, what drives you?

“Every day is different. And I’m still passionate about it. We are an ageing population, and what is shocking, particularly with macular disease, is that someone may have worked for 40 years and they’re looking forward to what comes next – whether that’s retirement with grandchildren and family, or taking on a new career or new direction – and you get hit with this condition that takes away your central vision and makes all those dreams and aspirations much more difficult to achieve.

“As with lots of your members, it’s amazing how well many of them manage with their sight loss, but it’s a cruel fate that so many of them, having worked for years and years, are then faced with this condition.

“So that’s what still drives me. The key thing is we must get patients in, and that’s a combined effort. If you notice distortion in your vision, you must go to your high street optician, most of whom are highly trained in spotting the signs of macular disease. If we can get patients in quickly, we can get them

access to the best treatment – if we can fund the best treatment.”

And that’s where the Macular Society is needed.

“Absolutely. The Macular Society is considered globally as a world-leading patient advocacy group, and that’s not only when it comes to informing and pushing the government for more investment, it’s also supporting patients in their homes, helping, advising and educating them, and then of course funding the research to find a cure.

“The Macular Society is a voice for a silent disability. You’re listening to people who are struggling; you’re representing them. You’re addressing the problem of visual disability, and you’re doing that very well.”

You say this is an exciting time in ophthalmology – can you tell us why?

“It really is an exciting time. There’s such an explosion of interest. I

think we’re certainly on an exponential growth in new treatments, new

approaches and new research to help patients.

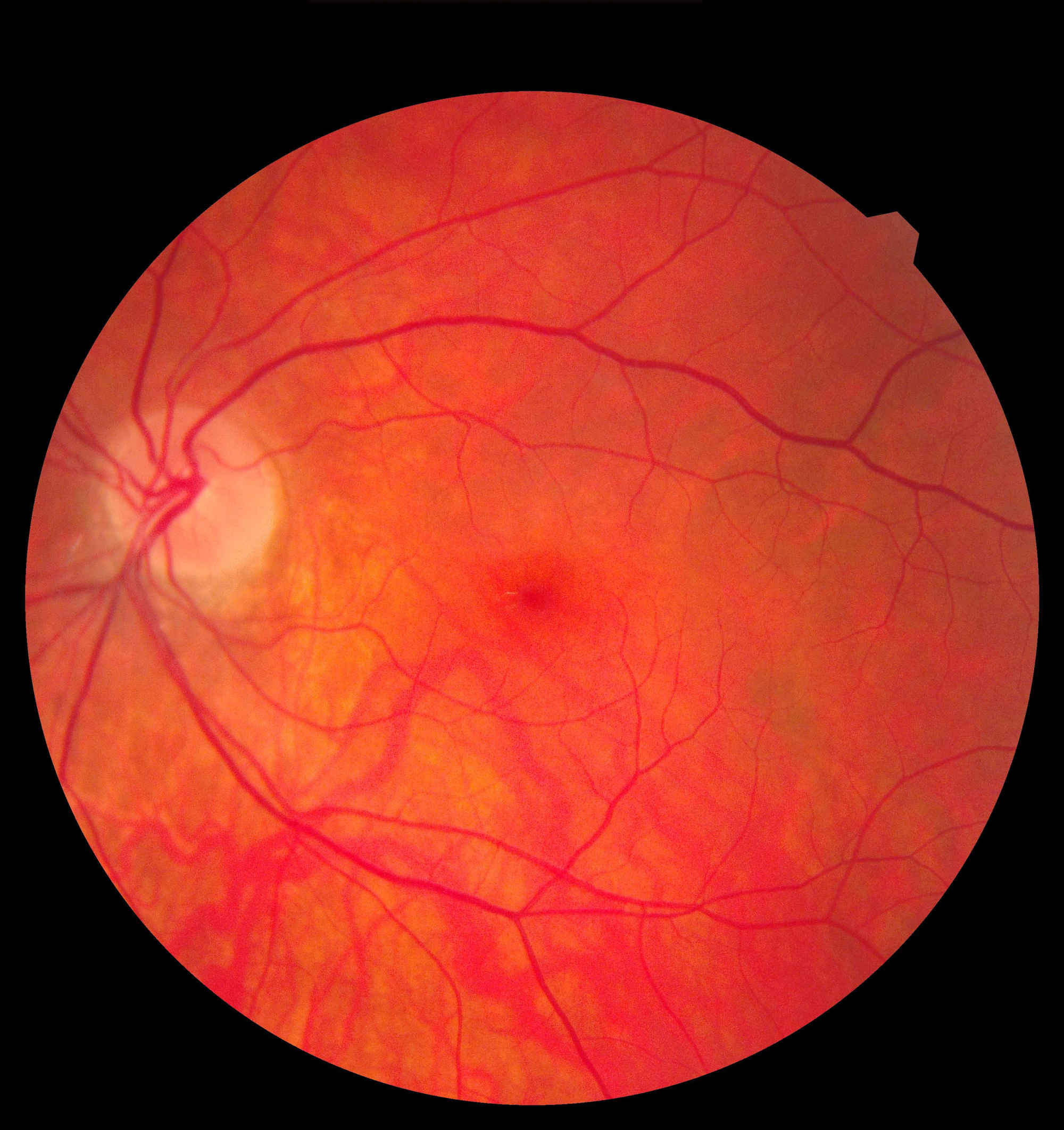

“Take, for example, an OCT scan – one of the best ways of examining the back of the eye and picking up early fluid. This is a technology that didn’t even exist 25 years ago, and since then it’s come into hospitals and the application of this technology enables us to treat patients earlier and better – it’s fantastic.

“At the other end of the spectrum, we’ve got dry macular degeneration, this loss of central vision which we’re struggling to halt or slow down. But now we can take a new gene which produces a complement factor (I) protein, we can put that in a virus and grow it in the virus, and we can then put that viral vector in the retina. That new gene can be incorporated into our own eye’s biology and start producing the chemicals to slow down geographic atrophy and dry macular degeneration.

“There are a multitude of potential opportunities and developments, so this really is a time that you want to be involved. I was thinking of retiring a few years ago, but now I’m so excited about the treatments we can offer patients, I’ll probably stay another few years!”

What are your hopes for a cure in the future?

“The future is bright with hope, but we need people to fund more research to bring a cure closer. Macular disease is growing every year, as we’ve got an ageing population – it’s getting worse. Research needs income, and legacies

are critical in that respect, but it doesn’t need to be a million-pound legacy, does it? Every legacy makes a difference.

“We’ve got the potential and opportunity to save people’s eyesight. We have solutions, we have more treatments, and we have more hope. We’ve got more hope than we’ve ever had in the history of ophthalmology.”

We'd love to hear from you

By leaving a gift in your Will to the Macular Society, you're giving hope for a cure to every person diagnosed with macular disease.

For a copy of our free Gifts in Wills booklet or to ask about making or updating your Will for free through the Macular Society, please fill in the form or get in touch with Julie or Katherine on 01264 322 410.

Thank you for Beating Macular Disease

If you’re considering leaving a gift or have already left a gift in your Will to the Macular Society, thank you so much. Your generosity is hugely appreciated, and your thoughtful gift will help create a future without macular disease.